😱😻😱

There are no better words to what I'm feeling right now

One of my “evil genius” marketing plans (OK, “slightly maladjusted curmudgeon”) was to get an A-Lister SF&F author to write the introduction. Little did I expect what came next…

Harry Turtledove, the grandmaster of alternate history, winner of the Sidewise Award for Alternate History (as well as Hugo, Nebula, and Prometheus awards), and a PhD specialising in Roman and Byzantine history, had this to say about In Victrix:

Assaph Mehr’s Egretia is Rome as the Romans themselves imagined it to be. Magic really works. Curses curse, love philtres create love, oracles do predict the future, and on and on. The genuine Romans enacted laws against magic not because they thought it was a fraud but because they thought it wasn’t, and feared what it would do if widely practiced.

Throw in the late Republic’s baroque and richly corrupt electoral system, a kidnapping or two, love affairs, bad guys, some good guys who are just about as bad as the baddies, and a coctus (hardboiled, to you) detective who knows all the angles and how to play them as well as any master of geometry, and you’ve got quite a book. I enjoyed it a lot. I expect you will, too.

I’m over the moon with a pride! 😲🥰😲🥰 My fantasy version of Roman life has so far been reviewed — and approved! — by at least three history PhD’s. Even the magic of the Romans in the series matches the best literature about it!

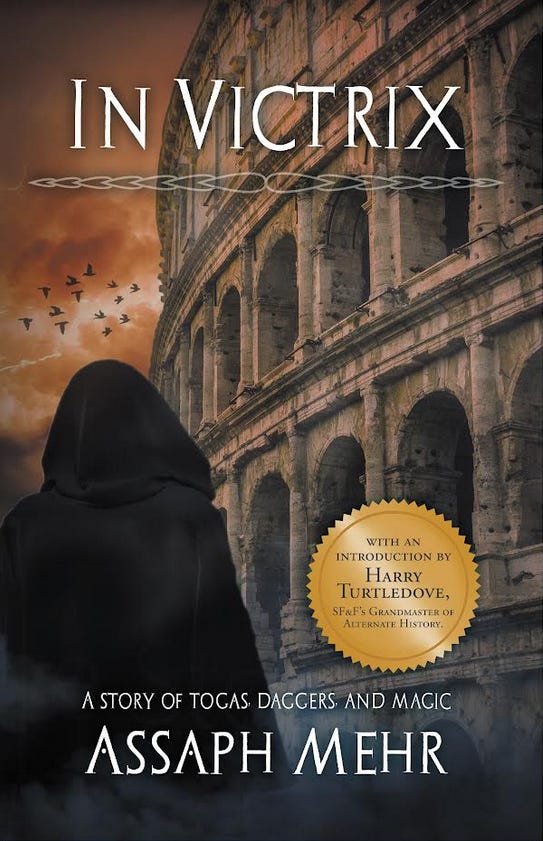

I’ve reproduced Harry’s introduction below in full, setting the (historical) scene for the major themes in the novel. If you can’t wait, In Victrix is now available for Kindle pre-orders on Amazon with paperback coming soon — just finalising the gorgeous cover below 😍 — so you can jump right there:

Until next time,

Videas Lumen!

Assaph

What I most enjoy about In Victrix is that Assaph Mehr’s Egeria is Rome as the Romans themselves imagined it to be. Magic really works. Curses curse, love philtres create love, oracles do predict the future, and on and on. The genuine Romans enacted laws against magic not because they thought it was a fraud but because they thought it wasn’t, and feared what it would do if widely practiced. Even early Christians didn’t oppose magic because it was ineffective, but because it was, in their view, impious.

You will also learn a lot about how many obscure, little-known aspects of Roman society. You’ll pick up some handy Latin profanities and obscenities, for sure. If, just to give one example, you’re confused about the distinction between irrumatio and fellatio, you won’t be once you get through the book. You’ll also soak up quite a bit about the Romans’ language in general. Mark Twain famously said he would sooner decline two beers than one German adjective, and the sentiment applies all the more to Latin, which has more cases, each with its own particular endings. Assaph navigates all this with grace and ease.

And you will find out as much as anybody modern knows about chariot racing and the gladiatorial games, the two main spectator sports in Roman times. Think of association football and cricket in most of the Commonwealth, or the NFL and the NBA in the United States. Star performers in the races or the games grabbed fame and wealth and women the same way modern sports stars do, and ran through them just as fast as stars do today. Except for the cars, footballer George Best’s quote applied as well to 2,000 years ago as it does now: “I spent a lot of money on booze, birds, and fast cars. The rest I just squandered.”

There was one major difference between sports then and sports now, though. You could die much more easily then than you can now. Gladiators seldom fought to the death, but seldom did not mean never. Chariot drivers carried a sharp knife to cut themselves free of the leather lines securing them to their car and the horses in case of a crash, but that didn’t mean they could always use them. Getting trampled or dragged by your own team or an opponent’s was an occupational hazard. Something else to remember is that chariots, like today’s racing cars, were as light and flimsy as they could be while still holding together, and for the same reason: to go really fast.

When we touch on gladiators and charioteers, we also touch on slavery, because most of them started their careers as slaves. Rome during the late Republic and early Empire was one of the few societies where slaves played a vital role in the economy. The others that jump to mind are Athens during the time of its greatest glory (the silver that built the Athenian fleet that beat the Persians at Salamis came from the mines of Laurion, mines worked by slaves whose life expectancy was measured in weeks--getting sent to the mines was a virtual death sentence for slaves throughout Greco-Roman history); Brazil up through emancipation there in the late nineteenth century; and the United States to the end of the American Civil War, along with the adjacent islands in the Caribbean.

Slavery in the ancient world had some things in common with the more modern New World institution; it also has significant differences. That a person was a slave if his or her mother was a slave was true in both ancient and modern times. It could lead to… interesting situations, as when Founding Father Thomas Jefferson took as his mistress his late wife’s younger half-sister, and kept both her and her children by him in bondage. A slave was also property under both systems--the first chapter of the Lex Aquilia, dating to the third century BCE, discusses damages due against someone who has killed cattle or slaves.

But slavery in the ancient world wasn’t based on race. That made it much harder for ancient owners to regain their property if it decided to abscond with itself. Slaves in Greek and Roman times were people whose ancestors were unlucky enough to be hungry enough to need to sell themselves so they wouldn’t starve, to be captured by bandits and sold into slavery, or to be taken by the victors when the towns they lived in fell. Many of them were educated people: doctors, scribes, artisans. They often continued to ply their old trades, giving most or all of what they earned to their masters. But they had some hope of eventually saving enough money to buy their own freedom.

Manumission of slaves was more common in the ancient world than in the more recent New World. Not least because ancient slaves weren’t obvious by eye, they fit into society more readily than freedmen of African descent did in the Americas. Manumitted slaves kept certain obligations to their former owners; they were clients to the patrons who had once owned them. They also kept certain legal disabilities. They couldn’t become magistrates or Senators, for instance. But, during the early Empire, freedmen and their descendants dominated the imperial civil service, and some became immensely rich and powerful. Petronius’ Satyricon goes into amusing detail about one of these.

Throw in the late Republic’s baroque and richly corrupt electoral system, a kidnapping or two, love affairs you won’t be looking for (I’d say you won’t see coming, but you’d hit me), bad guys, some good guys who are just about as bad as the baddies, and a coctus (hardboiled, to you) detective who knows all the angles and how to play them as well as any (enslaved) master of geometry, and you’ve got quite a book. I enjoyed it a lot. I expect you will, too.

— Harry Turtledove, California, July 2024

What great news! No wonder you're over the moon! Congratulations for this awesome review!

Will you be releasing an ePub version? Perhaps via Kobo or direct from your storefront?

Unfortunately, I no longer am able to purchase from Amazon and convert to ePub as I did with your previous releases. [TLDR] Amazon now prevents downloads except using the latest version of the Kindle for Mac app and the resulting file is basically not convertable.